MATE 664 Lecture 04

Introduction to Diffusion

- Slides 👉 Open presentation🗒️

- PDF version of course note 👉 Open in pdf

- Handwritten notes 👉 Open in pdf

Recap of Lecture 03

Key ideas from last lecture:

- Entropy flux and production

- Rewritting entropy production in flux and driving force terms

- Direct and coupling coefficients

- Analysis of several cross-coupling effects in material science

Learning Outcomes

After today’s lecture, you will be able to:

- Identify driving forces and fluxes for diffusive mass transport

- Derive Fick’s first law from irreversible thermodynamics using chemical potential

- Estimate magnitudes of diffusivity in gases, liquids, and solids

- Explain temperature dependence of diffusivity using Arrhenius-type relations

- explain the thermodynamic origin of self-diffusion

Recap: Driving Forces in Irreversible Thermodynamics

entropy balance: \[ \frac{ds}{dt} = -\nabla \cdot \vec{J}_s + \dot{\sigma} \]

entropy flux: \[ \vec{J}_s = \sum_i \frac{\psi_i}{T}\vec{J}_i \]

entropy production: \[ T\dot{\sigma} = -\sum_i \vec{J}_i \cdot \nabla \psi_i \ge 0 \]

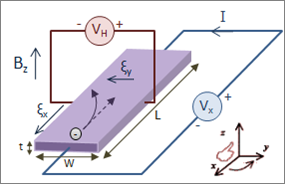

When Do \(\dot{\sigma}\) Diminish? Orthogonality of Flux and Driving Force

We will show one example that has non-trivial solution to \(\dot{\sigma} = 0\)

- entropy production vanishes if: \[ \vec{J}_i \cdot \nabla \psi_i = 0 \]

- Example: Hall effect

- Current flows while electric potential gradient is orthogonal

- Generalized for thermomagnetic and galvanomagnetic effects (Callen Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 1349)

- Magnetic field induced symmetry breaking

- \(L_{ij}(H) = L_{ji}(-H)\)

Chemical Potential as Driving Force

Consider one chemical species with chemical potential \(\mu\)

Definition: \[ \mu = \left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial N}\right)_{S,V} \]

\(\mu\) represents energy cost of adding more molecules

Diffusion driven by gradients in \(\mu\)

See analog to a water tank in handwritten notes

Entropy Production and Mass Flux

Entropy production due to diffusion: \[ T\dot{\sigma} = -\vec{J}_m \cdot \nabla \mu \]

Linear law: \[ \vec{J}_m = -L_{MM}\nabla \mu \]

\(L_{MM}\): phenomenological mobility coefficient

From Mobility to Fick’s Law (Determine \(L_MM\))

See analog in handwritten notes

Force balance and drift velocity (\(M\): mobility): \[ v = M \nabla \mu \]

Mass flux: \[ \vec{J} = c v = -M c \nabla \mu \]

Diffusion coefficient: \[ D = M k_B T \]

Chemical Potential in Mixtures

See analog in handwritten notes

For constant \(T,P\): \[ \mu_i = \left(\frac{\partial G}{\partial N_i}\right)_{T,P} \]

Chemical potential in a mixture solution: \[ \mu_i = \mu_i^0 + k_B T \ln \gamma_i x_i \]

activity coefficient \(\gamma_i = 1\) for ideal solution (Raoult’s law)

Fick’s First Law

Substitute \(\mu_i\) into flux. For species \(i\) \[ \vec{J} = -D \nabla c \]

Assumptions:

- ideal solution

- constant \(T\)

- isotropic medium (\(D_{\alpha \beta}=D=\text{Const}\))

concentration gradient is a special case of \(\nabla \mu\)

What Does Diffusivity Depend On?

- temperature

- concentration

- spatial position (??)

- general diffusion driven by \(\nabla \mu\)

- Fick’s law valid under restricted conditions

Fick’s Second Law

Mass conservation (no source term) \[ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = -\nabla \cdot \vec{J} \]

Substitution: \[ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (D \nabla c) \]

If \(D_i\) is constant: \[ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = D_i \nabla^2 c \]

- \(\nabla^2\): Laplace operator

One-Dimensional Diffusion in Isotropic Homogeneous Medium

1D equation: \[ \frac{\partial c}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 c}{\partial x^2} \]

Steady state: \[ \frac{\partial^2 c}{\partial x^2} = 0 \]

- Linear concentration profile!

Physical Meaning of Laplace Operator

\(\nabla^2 c\) measures curvature (sort of…)

Steady state implies zero curvature

Transient diffusion requires nonzero curvature

Curvature and Second Derivative

concave profile: \[ \frac{d^2 c}{dx^2} < 0 \]

convex profile: \[ \frac{d^2 c}{dx^2} > 0 \]

curvature determines smoothing direction

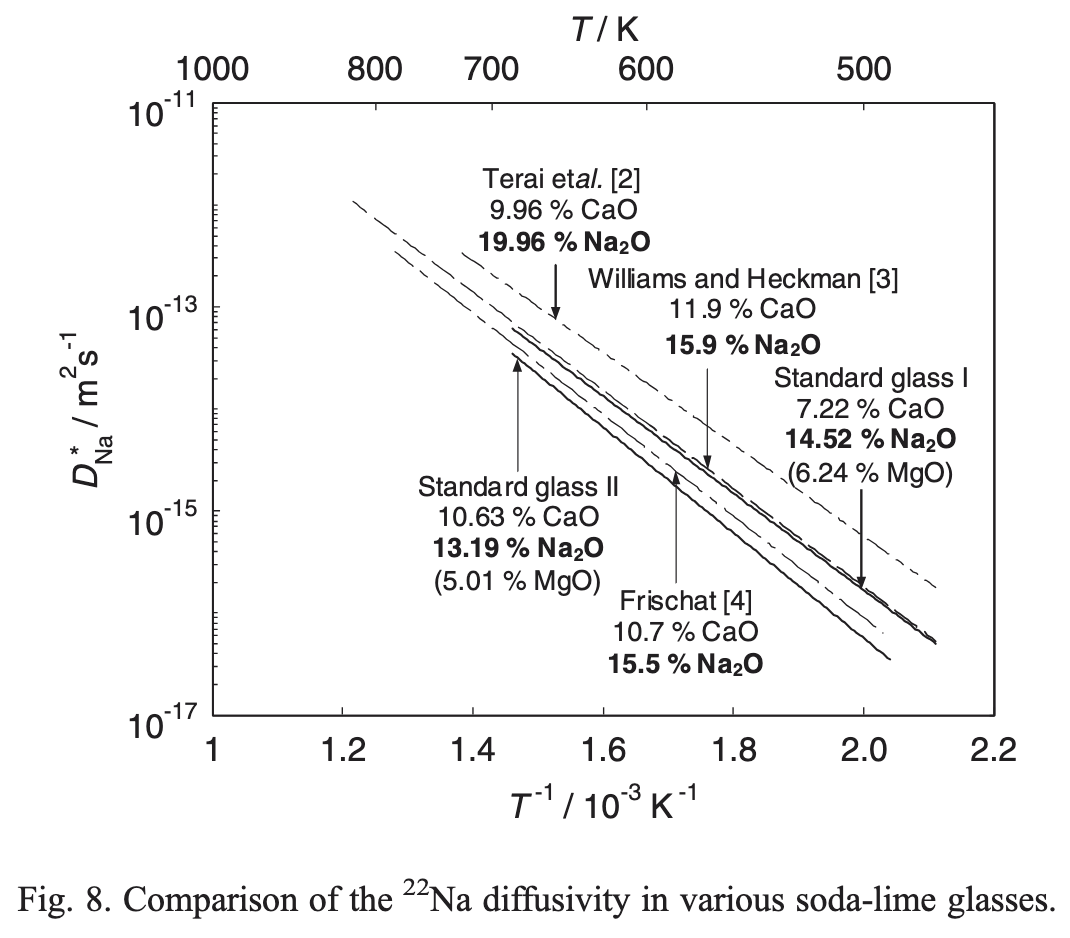

Typical Magnitudes of Diffusivity

- gases: \[ D \sim 10^{-5}\ \mathrm{m^2/s} \]

- liquids: \[ D < 10^{-9}\ \mathrm{m^2/s} \]

- solids: \[ D < 10^{-13}\ \mathrm{m^2/s} \]

Typical \(D\) Range

A Common Misconception

Search for any youtube video with “diffusion experiment dye”

Can we verify whether the scenario seen is Ficknian diffusion?

Diffusion vs Convection Length Scale

Length \(L\) traveled in time \(t\):

- Diffusion: \(L = 6\sqrt{D_{AB}\,t}\) (Einstein, ~1905)

- Convection: \(L = v_m\,t\)

What is typical \(D_{AB}\) in a liquid?

- Often \(D_{AB}\sim 10^{-9}\) to \(10^{-10}\,\mathrm{m^2/s}\)

Assuming \(D_{AB} = 10^{-10} \mathrm{m^2/s}\) \(v_{m} = 10^{-3} \mathrm{m/s}\)

Temperature Dependence of Diffusivity

- Arrhenius form: \[ D = D_0 \exp\!\left(-\frac{\Delta H^a}{k_B T}\right) \]

- \(\Delta H^a\): activation enthalpy

- Why do we measure \(\Delta H_a\), not the \(\Delta G^a\)?

- How can you read the plot?

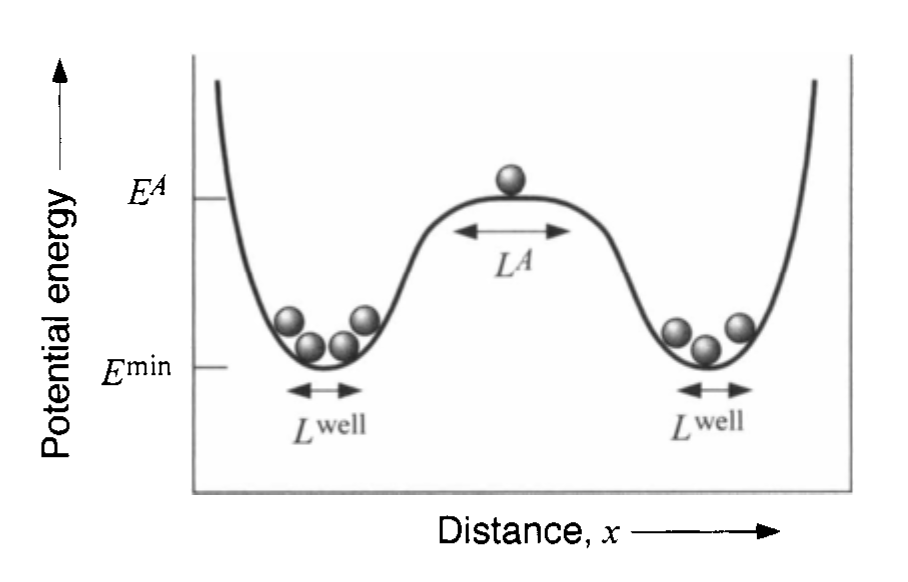

Physical Interpretation of Activation

- atoms hop between sites

- energy barrier must be overcome

- jump frequency: \[ \Gamma = \nu \exp\!\left(-\frac{\Delta G^\ddagger}{k_B T}\right) \]

- diffusion proportional to hop rate and distance

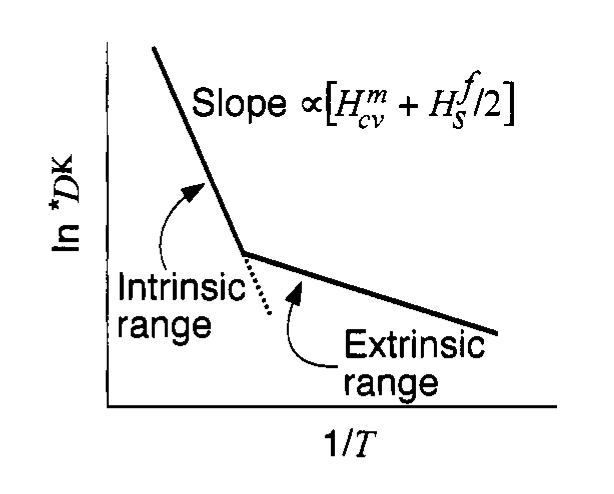

Multiple Diffusion Mechanisms

- Different diffusion paths

- Different activation energies

- Dominant mechanism controls slope of \(\ln D\) vs \(1/T\)

Diffusion in Gases

Kinetic theory description

Chapman–Enskog result: \[ D \propto \frac{T^{3/2}}{P} \]

Collisions limit transport

Diffusion in Liquids

Stokes–Einstein equation: \[ D = \frac{k_B T}{6\pi \eta r} \]

\(\eta\): viscosity

\(r\): particle radius

Is it accurate enough in polymer solutions?

Diffusion in Solids

- Diffusion in solids is much more complex!

- Discrete lattice sites

- Mechanisms (non-exhaustive)

- Vacancy

- Ring mechanism

- Push-out mechanism

- Interstitial

- Strong temperature dependence

Vacancy Diffusion Mechanism

- Atoms exchange with vacancies

- Jump only if vacancy is adjacent

- Vacancy sources:

- Surfaces

- Grain boundaries

- Dislocations

Types of Diffusivity

As the previous example of diffusion + convection video shows, the measurement of diffusivity really depends on which reference frame we use.

- Self-diffusivity \(D^*\)

- Intrinsic diffusivity \(D_i\) (lattice frame / C-frame; \(\mathtt{C}\) 👉crystal)

- Inter-diffusivity \(\tilde{D}\) (laboratory frame / V-frame; \(\mathtt{V}\) 👉volume-fixed)

Measuring Self-Diffusion

Isotope tracer experiments

Lattice constraint: \[ c_i + c_i^* + c_v = \text{const} \]

- General “network-constrained” problem

Vacancy concentration often at equilibrium

- Vacancy balance with the source (surface / grain boundary / dislocation)

Flux Relations in Network-Constrained Systems

- Flux driven by chemical potential differences (1D)

Non-radioactive species: \[ J_i = -L_{ii}\frac{\partial (\mu_i - \mu_v)}{\partial x} -L_{i{i}^*}\frac{\partial (\mu_{i^*} - \mu_v)}{\partial x} \]

Radioactive species: \[ J_{i^*} = -L_{{i^*}{i}}\frac{\partial (\mu_{i} - \mu_v)}{\partial x} -L_{{i^*}{i^*}}\frac{\partial (\mu_{i^*} - \mu_v)}{\partial x} \]

Vacancy (zero-flux, why?): \[ J_v = 0 \]

Vacancy Equilibrium Assumption

- \(\mu_v = \text{const}\)

- \(J_v = 0\)

- total flux balance: \[ J_i + J_i^* + J_v = 0 \]

Resulting Self-Diffusion Flux

- Chemical potential gradient: \[ \frac{\partial \mu_{i^*}}{\partial x} = k_B T \frac{1}{c_i}\frac{\partial c_i}{\partial x} \]

- Self-diffusion coefficient: \[ D^{*} = k_B T\left(\frac{L_{ii}}{c_i} + \frac{L_{ii^*}}{c_{i^*}}\right) \]

Why Self-Diffusion Occurs

- No macroscopic concentration gradient!

- Chemical potential varies locally

- Random walk lowers free energy

- Entropy maximization drives motion

Summary

- Diffusion is driven by chemical potential gradients

- Fick’s laws follow from irreversible thermodynamics

- Laplace operator reflects curvature and smoothing

- Diffusivity varies strongly with phase and temperature

- Self-diffusion exists even in homogeneous systems

Footnotes

Solid. State Ionics 2006, 177, 2839↩︎